Originally published on Sole

The co-founder of Black Lives Matter on the impact of “influencer activism,” performing patriotism, and the realities of demanding a better world.

“Black Lives Matter means to me that Black people deserve respect and justice — to live a life full of dignity and a life where we actually thrive.” – Ayọ Tometi

From the #MeToo movement to the #FreeBritney campaign, concerned citizens the world over are taking to social media to express their discontent with the status quo — with tangible effect. A welcomed change to the passivity of the past, but one that blurs the lines of interest and expertise. The noun “activist” is now spreading across Instagram bios like wildfire, while only a handful of self-declared activists have the training, capacity and commitment to work backwards and deeply connect with those whose cause they claim to carry.

Activists everywhere are sounding the alarm on the horrors of systemic violence, but there are far fewer organisers operating at the roots. Even rarer are those who have managed to do both. Ayọ Tometi is one of those select few.

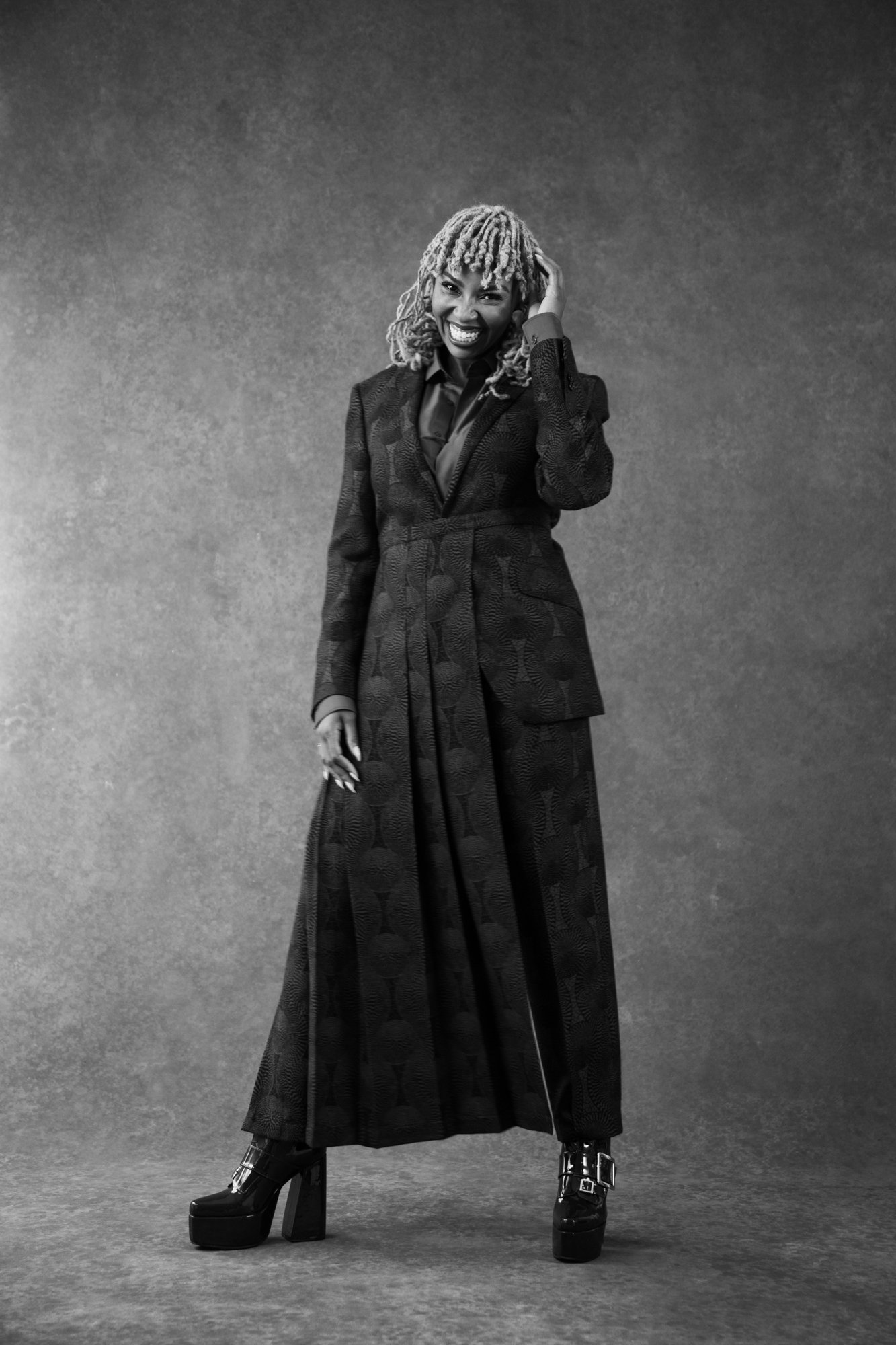

On a typically muggy day in East London, she hopped out of a black Uber in an all black outfit and a suede camel coat draped around her shoulders. Even from behind her face mask, she emanated a warmth any Londoner walking by could immediately identify as foreign. Despite her American elocution, she would remind us all moments later that she is firmly Nigerian first. Inside the minimalist Hackney Wick studio, with the team circled around her, she made an announcement. She would no longer be known as Opal and is now publicly claiming her traditional name Ayọ; used by her close loved ones and from this year onwards, the world.

The Yoruba word for “joy”, her name had served as a secret source of strength which had constantly connected her with the heart of her community work. Not a conceptual political goal, but the deep-seated belief that joy is the birthright of every Black person. “I felt I had to go a layer deeper because for me the work is spiritual; it’s cultural,” Ayọ said. “I wanted to be more unapologetic about what it is I’m about — what I’m aiming for — which is joy for all of us.”

Hours of shooting sped by as she stood tall, smiled and danced in front of the camera to the persistent bump of Afrobeats. First against the earthy bespoke moss-green backdrop and later in front of her favourite colour — a deep, sunflower yellow. The colour is fitting in many ways. It’s the shade closely associated with the Yoruba Goddess Oshun, the deity of love, healing and fertility. It also harks back to a critical moment that marked her upbringing in Phoenix, Arizona. A realisation of “otherness” that every non-White immigrant in the West has at some point in their life, and one that Ayọ would cling onto as an intimate anecdotal signpost of where her work would take her.

Ayọ’s father worked as a mechanic for some time repairing used cars to sell within immigrant circles. Eventually, he restored a vintage mustard yellow Mercedes Benz for himself. The memory of her father’s smooth ride brought a mischievous smile back to her face as she recalled it — “let me tell you, if I could have that car right now…” But of course the story of the Black Nigerian immigrant driving an eye-catching yellow Mercedes in the Republican state capital takes a dark turn. The unapologetic pride with which her parents wore their traditional Yoruba dress could not translate to her father’s mode of transport. She remembers him being pulled over by police at least a dozen times. “There was a time where he was pulled over and three or four other squad cars pulled up and he was just like ‘enough!’. He was frightened. He was scared out of his mind. So he decided, ‘you know what? The risk is too much. It’s too great.’” He ended up retiring the car — a source of pride and personal effort — and instead, drove around Phoenix in a beat up white pick-up truck. While still racially profiled here and there, he wasn’t stopped as much.

As the eldest of three siblings, Ayọ had a front row seat to the issues experienced by her extended family and the wider immigrant community. “There were always these little flash points,” — checkpoints that anchored her attention back to immigrant rights and systemic oppression time and time again. A widowed aunt that was deported back to Nigeria leaving behind four daughters that were salvaged from foster care by the community, and a devastated best friend who had to move in during high school because her mother was deported. Ayọ watched survival mode set in. The people she loved — many of them proudly and loudly Nigerian — had started to don a costume of “American-ness” just to get by. “It’s not that they were performing because they didn’t believe or value the country, but [because] they had to show a certain side of themselves in a very caricature-like manner in order to be seen.” As time went on, tension heightened. After the cataclysmic aftershocks of the 9/11 Twin Tower attacks, she watched extreme islamophobia force the family of her Jordanian best friend to do the same. Labelled terrorists, Ayọ saw first hand how they had to “perform patriotism…they started wearing flag ribbons. They’re painting their home red, white and blue. They’re doing all the things to perform, just to keep themselves safe.”

Coming of age against the backdrop of dizzying identity politics and state-endorsed alienation, she launched into community work in high school and more formally at the University of Arizona. Ayọ spent years living close to the US-Mexico border studying history and stayed on to earn a Masters of Arts in communications & advocacy. During her time there she became a leading architect in the Black-Brown Coalition of Arizona; organising large scale mobilisation events and sharpening her calls to action. With the image of her father’s yellow Benz emblazoned in her mind, she rallied against the formalisation of racial profiling under the legislative label of “immigration enforcement.”

Armed with these experiences, Ayọ moved to New York City and kept racial injustice and immigrant rights at the heart of her work. She went on to become the Communications Director, co-Director and eventually, Executive Director of the United States’ first national immigrant rights organization for people of African descent: the Black Alliance for Just Immigration (BAJI). At its helm, she led the first Black rally for immigrant justice and the first Congressional briefing on Black immigrants in Washington D.C in 2013. A long overdue milestone in a country with an ever-growing Black immigrant population of an estimated 4.2 million. “My organisation [had] the word Black in it which was very rare for any organisation to have because it was not seen as what you do.” Her work at BAJI seemed to foreshadow the unapologetic banner she would later help imprint and sear into popular consciousness. “We have to name ourselves, we have to name the issue. There was something about that – Black Lives Matter.”

“I was with another fellow friend Kyra, also a community organizer. We broke down under the streetlamp for a while and then eventually we peeled ourselves away. I went home and cried.”

Merely months after she rallied hundreds of Black immigrants from Africa, the Caribbean and Latin America to march to the capital for the first time and visit congressional offices, there was another turning point. In July 2013, after closely following the horror story of 17-year old Trayvon Martin — an unarmed Black teenager shot and killed by George Zimmerman — news of the trial’s results landed like a tonne of bricks. “I had just watched the film Fruitvale Station, which is the story of Oscar Grant in Oakland, California, being killed by police on New Year’s Day. I was feeling so raw, so emotional and walked out of the movie theater and then saw the texts and the tweets saying that George Zimmerman was being acquitted. I broke down.” A pained glaze came over Ayọ’s eyes as she described the moment. “I was with another fellow friend Kyra, also a community organizer. We broke down under the streetlamp for a while and then eventually we peeled ourselves away. I went home and cried.”

Seeking comfort from other grieving friends online, she came across a Facebook post from fellow community worker Alicia Garza. Ayọ called it a “A love letter to Black people,” and at the end it read: “I love us. Our lives matter.” and in the comments Patrisse Cullors wrote #BlackLivesMatter. It’s a story she’s told many times before but the look on her face seemed just as inspired as it must have been that day in 2013. “There was a moment. It just hit me.” In that same moment, she picked up the phone and called Alicia and Patrisse — both immersed in their own community organising efforts at the time — with an urgent plea; “we need to build something bigger than what we are doing individually.” They were on board and Ayọ scrambled to register BlackLivesMatter.com and start up their social media pages. Her hefty communications training was in full swing. “I then sent out a mass email blast to a bunch of our community organiser friends and said ‘hey, I know you are all doing your respective organising from housing to jobs…but let’s start using this banner as a collective of Black Lives Matter and start sharing your stories of what you’re doing.’”

A year after it’s establishment, Ayọ, Alicia and Patrisse used their collective reach to get five hundred people to Ferguson, Missouri in the “Black Lives Matter Freedom Ride” to join protests denouncing the police killing of Michael Brown, in his hometown. “At the time people were saying — ‘well, we know Ferguson is everywhere. This is not a unique experience to this city. We know that people are being killed in New York. We know people are killed in D.C., we know people are killed in Louisville — not even just in the country, in the UK and so on.’ Folks began to connect the dots and see that there was something more to be done.” The opportunity for coordinated action against racial injustice would unfortunately arise time and time again. In 2015, it was the suicide of Sandra Bland in her police cell. In 2016, Alton Sterling — and in between many more other innocent Black people killed by state-endorsed violence across America.

Then, in the throes of a global coronavirus pandemic, there was the George Floyd murder in 2020. The horrific video of his brutal strangulation at the knee of police officer Derek Chauvin was shared by millions worldwide and ignited the largest wave of protests in American history. Choking on the painful memory of his death, a day after his birthday, Ayọ said: “In this time where what was being touted was ‘we are all in this together…we’re going to handle this together…’ The fact was that we couldn’t. We weren’t. We are not all in this together.”

Long before the vaccine roll-out, as governments were asking people to isolate at home, analysts estimate up to 26 million people in the country participated in BLM demonstrations, protesting George Floyd’s death in 2020. On June 6th alone, half a million people took to the streets in 550 locations across the US.

Black Lives Matter has become a global slogan to fight selective humanity and uplift Black lives to the base level of respect. Once perceived as a radical statement; now blazoned in LED lights across a huge billboard in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, on picket signs on the manicured front lawns of homes in the suburbs of Baltimore and on flags hanging out of windows in any large American city. After George Floyd’s brutal and bold-faced murder, silence became a part of the problem.

It has since become a global network with more than 40 branches sprouting up all over the world. Each local chapter operates independently but is expected to embrace the BLM principles rooted in empathy, inclusivity and restorative justice. In Europe, it consolidated Black activists fighting for better representation in government, constitutional change and improved treatment of refugees. In Brazil, it became a galvanised, modern iteration of grassroots movements like Movimento Negro, fighting extreme police brutality since the late ‘70s.

“The system here has done so much to shut us up — to keep us down — because the quality of our possibility to self-actualize is directly tied to how people are treated around the world.”

But in a world where influencer activism is on the rise, meaningful action can be drowned out in a sea of noise. Last year, in the midst of initiatives around the unjust killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, there was a random and obscure trend circulating: posting a black square on Instagram. “Sometimes people make up these calls to action without consulting people who’ve been steeped in the work for decades. What would have been nice is to consult some people, check in and see what are the demands, what needs we really have, and let’s collaborate on a call to action that makes sense.” For Ayọ, the mere image of a black square was simply not enough — “I am somebody who is not about mere symbolic action, less substantive action. So there were some sets of actions behind the scenes around it but it really got lost in translation, and a lot of people did not do anything after the black square.”

No place has been victim to symbolic virtue signaling more than Africa, where the banner of “salvation” used to justify colonialism is now the umbrella for botched developmental aid efforts and western intervention. “Within our own home countries and the African continent, we may not value our lives in the same way…or we might still value the companies that are led by folks in different parts of the world — more so than our own.” While Black immigrants and slave-descendent populations across the diaspora celebrate the continent, security forces puppeted, postured and protected by regional and global powers kill pro-democracy protesters from west to East — Nigeria to Sudan. “There’s this value system and economic system that is still operational — that will exist whether or not the person is White. It’s more complex. It’s deeper. It’s more entrenched. We have to undo it — we have to.”

At the time of writing [Oct 2021], one year has passed since Nigerian security forces opened fire on unarmed protesters rallying against police brutality under the banner of the #EndSARS movement at the Lekki tollgate in Lagos. Many of those killed that day are still missing. In the same month of this haunting anniversary, a military coup was announced in Sudan resulting in another deadly crackdown on protesters calling for a transition to civilian authority and justice for the hundreds killed and disappeared throughout the 2019 revolution. The former is Ayọ’s home country and the latter is not, but both the #EndSARS movement and the #BlueforSudan campaign were propelled to the spotlight by the BLM U.S. channels. “The privilege of being people who are doing movement work in the U.S., or who first started in the U.S…if we’re effective here, it does have implications for people around the world.” A commitment to Black life that makes the work not only critical but a direct threat to the global system of oppression. “The system here has done so much to shut us up — to keep us down — because the quality of our possibility to self-actualize is directly tied to how people are treated around the world.”

It’s fair to say that there are many institutions, individuals and terrorists that want BLM to come to a screeching halt; and the very tools that have empowered the movement have also left its members vulnerable. “In older times, we would have been in obscurity and kind of just doing what we needed to do. The stakes are higher. The use of technology and social media tools allows people certain access for more surveillance, more infiltration, a lot of other types of challenges.” Earlier this year, Ayọ’s fellow co-founder Patrisse Cullors was targeted by several conservative papers that falsely alleged she took a large salary from the foundation affording her the purchase of a large home in southern California — failing to mention that Cullors is releasing a second book and has a multiyear TV development deal with Warner Bros.

Smear campaigns aside, the organisation has also received reasonable criticism from grassroots organisers about financial transparency, decision making and accountability. According to information shared by BLM with Associated Press, the foundation took in more than $90 million last year and ended 2020 with a balance of more than $60 million — spending $21.7 million in grant funding to official and unofficial chapters and 30 Black-led local organisations. $8.4 million was declared to be spent on operating and administrative expenses, along with civic engagement, rapid response and crisis intervention activities in 2020.

Ayọ believes that the solution to combating disillusionment lies in fostering agility and building as you go along. “We’re having to experiment every single quarter, every single season. I don’t think there’s a time where that is not the case, especially because of how visible [we are] and how much money is now involved in our movements…there is no perfect recipe for how to do it. And I think as a result, that means there has to be [space] for honest conversations and collective reflection.”

Ayọ has dedicated the last two decades of her life to a path that is personal, universal, spiritual and professional. For the co-founder, Black Lives Matter goes beyond a cause or a narrative; it’s a way of existence. Even after stepping back from the day-to-day operations and channeling her energy into her new production company or her organisation Diaspora Rising, from her current homebase in Los Angeles, Black Lives Matter is an affirmation that she carries with her everywhere. An antidote to the devaluation dished out at Black people on a daily basis “Those three words are so powerful to me because they read both as an internal mantra of sorts and something that’s just very spiritual and intimate, but also as a demand like — we’re putting this on the society. We’re going to name the injustice that is occurring and we’re going to demand a better world.”

Back in the East London studio against the rich yellow backdrop, Ayọ laughed and spun around to the sound of Beyonce’s “Black is King”, exuding a joy that felt charged from within. Her life’s work brings her back again and again to devastating and anger-inducing injustice but feels fuelled by the purest force of all — love. “I just love people. I just love us. I’m here to celebrate our folks and that is what has led me down this journey — we’ve got to protect us. If we’re going to celebrate this, we have got to be alive for that celebration.”

Yousra Elbagir is an award-winning journalist, writer and producer. As a foreign news correspondent for Channel 4 News and VICE on HBO, she propelled underreported stories to the forefront of international media. From music radio documentaries to essays on identity politics, her work has been featured on the BBC, CNN, the Financial Times, the Guardian and many more.

Photographer Jameela Elfaki from Studio PI

Creative Direction & Production Sole

Assistant Nico Froehlich

MUA Karla Q Leon

Stylist Yasmine Sabri

Styling Assistant Romel Doyle